The afternoon after I got my first period, I bused home from school, called my mom at work to tell her the news, and then I took off my shoes and went directly to my bedroom to apologize to my wall of meticulously-hung Jonathan Taylor Thomas posters. I told him I was sorry, but something had changed and I was a woman now, and I couldn’t devote so much of my energy to being hopelessly in love with him anymore. I’d have to develop crushes on more appropriate, older men, like Rob Thomas, and continue playing with my prized Littlest Pet Shop collection only in private.

I was prepared for my period; I’d basically been waiting for it with waxing and waning enthusiasm for the past two years after our sex-ed presentation in 5th grade. We were separated by sex into different classrooms and given goodie bags full of various things like deodorant, pads, tampons, and pantyliners and given cursory anatomy lessons and explanations. I don’t remember much from it other than the sterility of the experience, but afterwards, some of the girls in class were really excited about getting their periods; others, not so much. Most of the excited girls just checked for any sign of pink in their underwear and surmised through the bathroom stalls whether their eyes were playing tricks on them, but one girl told me she actually wore a tampon every day, “just in case.” That worried little hypochondriac me because I took all the toxic shock syndrome warnings during the tampon unit very seriously.

Anyway, I was somewhere in the middle, already knowing it was going to happen and what to expect and being somewhat indifferent to it, but still excited about the idea of going through a traditionally symbolic change from childhood to “adulthood,” even if I didn’t feel at all womanly at the time. Actually, looking back it felt more like becoming a real teenager to me then, rather than a woman.

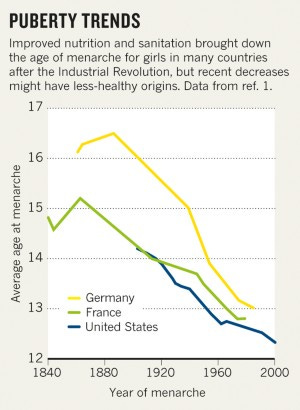

As I recall, they told us the typical age of a girl's first period was usually between 14 and 16, and that it was typically similar among women in the same family. Knowing my mom got hers at 10 or 11 (and my younger sister, later, at 11), I figured I'd be on the earlier end. I was right: it came during art class in 7th grade; I was 12. By that point, the age of girls’ first periods had already decreased from the 14 - 16 range long prior.

A(n alarming) number of years ago, I wrote this blog post, then a later follow-up, on my old blog, The Nice Feminist. The Discourse at the time was about hormones and other chemicals from various pharmaceuticals like birth control pills and antidepressants in the water and how they could affect women and the population at large, and I was big mad about it. I had used hormonal birth control (a pill, I don't remember which one anymore) for a few months a few years prior and had horrible side-effects and a doctor who seemed indifferent and didn’t provide me with much information at all, and no hint to the questions I didn't know to ask.

I eventually began to suspect that perhaps my sudden deep depression and other uncomfortable but otherwise unexplainable physical changes, things I’d never really experienced before, might be related to the hormonal changes in my body, and I did a little research. I was convinced enough at the correlation to stop taking the pill immediately, and my symptoms stopped just as quickly.

Anyway, I had a grudge, and my stepping into those waters with all of my self-righteous vitriol aimed at the women who use hormonal contraceptives for only contraceptive purposes unsurprisingly did not go over well, and the comments on the original post basically tore me to shreds, but that was somewhat common in this genre of blogging. I’m embarrassed at how poorly this rant was written, but I can't help but lol at my audacity:

But feminists of the so-called “third wave” or contemporary persuasion, for some reason, love the crap out of Big Pharma. You can’t pry those precious prescriptions for all of their many problems out of their claws. They can’t seem to grasp the idea that many prescription medications are bad for you, and bad for the environment. If they can grasp it, they try as hard as they can to find a reason why it would be wrong, immoral and sexist to ban them. Or, how, Who cares if it’s bad, what you said made me feel fat!

No wonder I got yelled at by everyone.

Underneath the biting sarcasm and snark, however, was a salient argument: basically that endocrine disruptors were, in fact, an increasing public health issue, and one that I was tired of hearing the feminist community dismiss as misogynistic whenever it was mentioned in a misguided effort to protect one of our first and most convenient contraceptive options. It threatened a revolutionary reproductive breakthrough that allowed women to control their reproductive lives without relying on or worrying about their male partners. An incredibly important breakthrough that forever changed the sexual and reproductive landscape. And, since then, many more breakthroughs have allowed for other types of contraception for both women and men (although still mostly women). Times are changing, we're learning new things, we can adapt. It's kind of a core tenant of progressivism.

Alas, endocrine disruptors in our environment are actually a legitimate and growing concern, and it’s not just because of birth control pills or trans and menopausal women’s estrogen supplements, but a wide range of pollutants that we now recognize as endocrine disruptors. And it seems at least somewhat convincing that this disruption is part of the many reasons why the age of young women’s first periods has dropped to record lows. Kids much younger than 12 are starting puberty these days, and when you consider that brain development and emotional maturity haven't caught up yet, the effects can be traumatic.

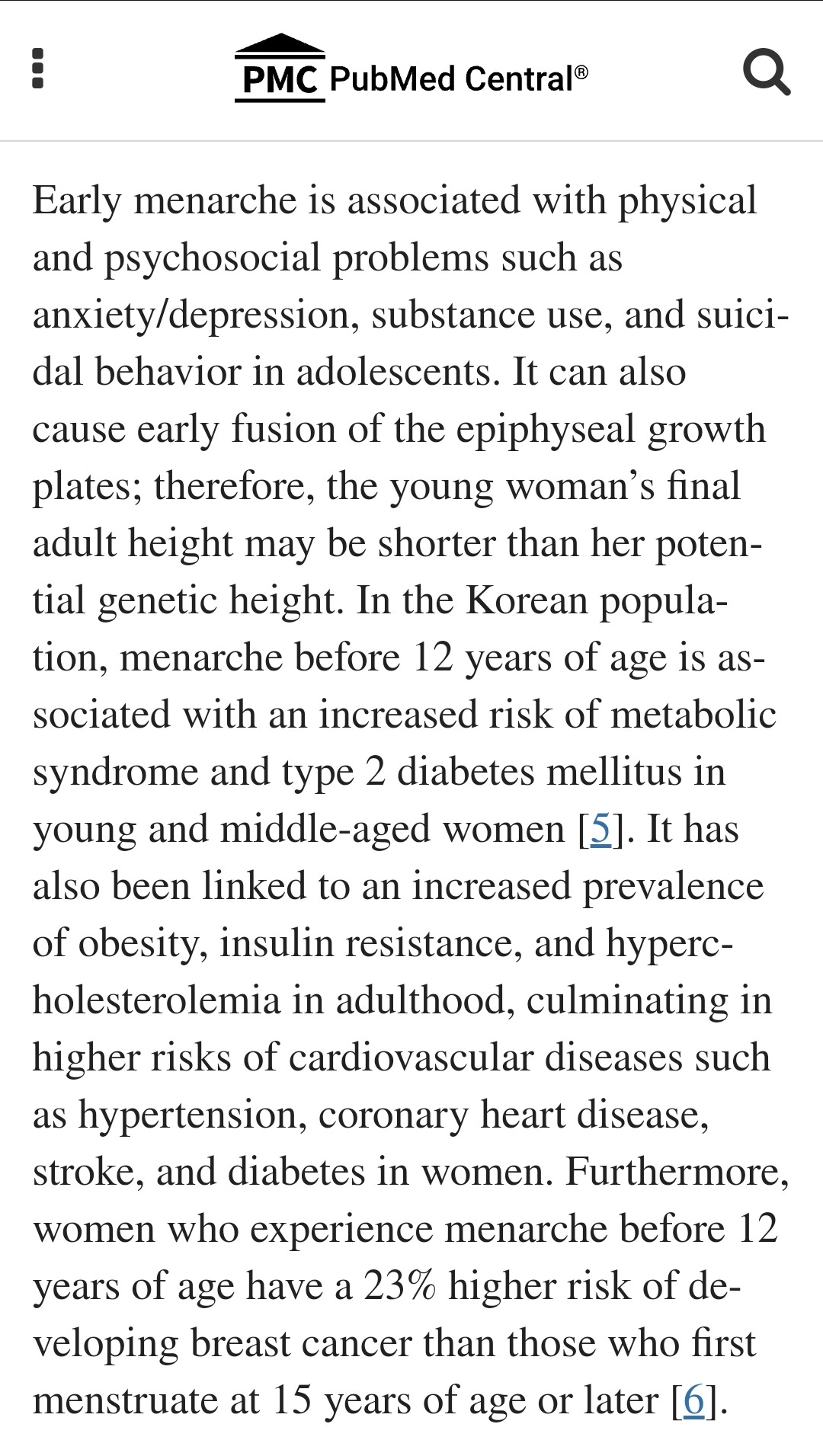

The potential negative effects on a girl who gets her first period before age 15 — let alone 8 or 9 — are numerous. From the article linked above:

Besides the health-related concerns, there are real concerns about the damaging effect earlier puberty has on young girls when it comes to their emotional state and social expectations and behaviors directed at them. They're growing into adult bodies they're not yet emotionally prepared for, and they're beginning to attract the subsequent kind of male attention that they're not ready for or know how to handle. This may cause a girl to grow to fear men and have a hard time trusting them later in life, it can cause her to jump too quickly into sexual situations she's not emotionally (or fully physically) ready for, it can cause undue hardship at school with all the baffling bullying that happens to girls who develop early and get called sluts just for having boobs.

…Speaking of boobs, for some of us, despite the harassment they could invite, getting them was a much bigger deal than getting our periods. Those were visible markers of growing up, and unlike periods, they did the opposite of gross out the object of most of our desires: boys.

The majority of girls in my peer group started wearing training or sports bras in 5th grade, so between 10-11. Of course these “training bras” were not real bras, exactly; they were probably invented for marketing purposes and entirely unnecessary, but you better believe every single one of us had a white, flat triangle little baby bra by the end of that year. You knew everyone had the bra not because of all the budding breasts visibly surrounding you, which did not really exist except on a couple girls, but because we did everything in our power to make sure you could see them. We all started wearing thin white shirts, or risked getting in trouble for breaking dress code by wearing a tank top with the strap deliberately hanging out in a way we hoped looked unintentional but definitely wasn't. Off-the-shoulder shirts became wildly popular among the Minneapolis 90s tween set. Most of us didn't have periods yet, but we did have sore and slightly swollen areolae(?) and a useless extra layer of fabric under our shirts to prove how grown up we were!

…As I was saying, the point is that no matter what's causing extensive early menarche in modern times, we're unlikely to be able to effectively remove endocrine disruptors from our lives without slow-going effort and endless political battles, so what can we do in the meantime to help these young girls?

wrote about this recently, and it’s something he’s talked about with many of his female podcast guests. He notes:Girls are getting their periods and developing secondary sexual characteristics (boobs) 1-3 years earlier than they “should be” biologically. But they can’t psychologically handle the stresses of incipient womanhood (menstruation, intrasexual competition, sexual attention from men) because they still have the mind of a little girl.

I’ve gotta say, this never really occurred to me. While it never felt like the age I got my period was unusually early since most of my peers got theirs roughly around the same time, it seems incredibly obvious now that such early sexual development — especially in the single-digit ages like we're seeing more of now — would be likely to cause the kind of trauma that can negatively alter a girl’s view of men for the rest of her life, and more broadly, negatively affect the overall relationship between the sexes going forward as it becomes the experience of entire generations of women. Consider my first reaction to getting my period: apologizing to teeny-bopper posters on my wall and being sad about my favorite toys. I was very literally a child. I was also a relatively late bloomer when it came to the boob area and also pretty scrawny, so I didn’t have to deal with a lot of the too-young sexualization other girls did (middle school kids literally thought I was a boy for half of 7th grade due to both my narrow and flat frame and the unfortunate timing of the movie Ghost and my insistence on getting Demi Moore’s haircut), but I can’t imagine how much worse and more terrifying it would’ve been if I had started receiving the kind of aggressively sexual attention from grown men even younger than I did.

Walt wonders if there might be any creative solutions to this growing problem:

Talk about your personal experiences, look through the many many many many studies on decreasing age of menarche and see if you can’t come to any novel insights, and propose some creative solutions. I don’t care how crazy these solutions are—literally any suggestion is appreciated, because we really need to get people talking about this.

I think I’ve got just the one.

When I was around 20 or so, a friend gave me the book The Red Tent by Anita Diamant. The book centers on the lives of the women in the Bible and, especially, the Red Tent, which is where the women would gather when they bled. It was a tent colored red for somewhat obvious reasons, filled with hay for the women to lay on to absorb their menstrual blood. While the history of the “menstrual hut” isn’t exactly one of female empowerment, there’s no reason it can’t be reimagined.

I'll be honest, I never actually finished the book, but I read enough to get the concept. The women in the tent would use the time to discuss their lives, marriages, give advice to the young girls, catch up on their knitting or whatever, everything you’d expect from a community of women who lived and worked among one another — and, as noted in the book, shared husbands — and to me then, it sounded… kind of wonderful. Wonderful, but also impossible. How would I possibly be allowed to take off work to go sit half-naked, free-bleeding on some hay with other menstruating ladies for a week? Every month?

Not to mention the backlash that would cause not only from men who don’t understand or who use the proposal as proof that women are inferior to them, women who are appalled that anyone could see themselves as incapable of work during that time, and others simply concerned with lost economic productivity, but what would it look like for women in their childbearing years? Like we were biologically incapable of work, like our uteruses were, in fact, holding us back? Would it set back the feminist movement another 50 years to admit that we might actually want an accommodation like that? That we might benefit from it?

I don’t really know, though. Maybe I don’t care if it makes us look “unproductive.” What if we just had a society that didn’t focus on that, instead? Easier said than done, but I’m in an optimistic mood.

What if we had a Red Tent clause in every employment contract and in every school?

Maybe it would say that, included in every female health insurance plan, is the optional entrance to a Red Tent of one's choice during the duration of your bleeding time1, up to 7 days (sorry, heavy bleeders, there has to be an arbitrary limit somewhere). It would be attached to a law that required employers to honor the usage of the Red Tent Tickets without retribution, and any resulting loss of productivity or wages would attempt to be rectified with stipends or subsidies or something from the Department of Health2. Maybe it would be treated economically and legally similarly to reservists getting time off to do reservist stuff. Idk, I'm spit-balling here. This is utopian armchair philosophizing and I'm not an economist.

The Red Tent culture could vary in time and commitment levels. Maybe most women would still go to work during the day, but choose to opt out of the rest of regular life afterwards and go straight to the Red Tent instead of her real home that week. This kind of Red Tenter would maybe be a single, younger woman without responsibilities tying her to her home, or maybe she's got a family and this week is her precious time away when her husband or someone else watches the kids and she goes to bleed on some hay with her fellow exhausted moms who suddenly love their periods because they get to have this special bonding time. Pass the bong!

Red Tents wouldn't need to be literal tents (although I think we should stick with the red motif, for sure). They could easily be wings (heh) in large hospitals, near maternity departments and made cozier and more service-oriented. They could be one of the never-ending ideas for what to do with all the abandoned old malls around the country.

Maybe some have a more spa-like experience that includes massages and yoga and salon services. Maybe some are more medicalized or trauma-informed for women with awful periods or endometriosis, or those that function similarly to support groups where women who aren't terribly into celebrating this part of womanhood can commiserate and offer one another emotional and material support.

Some could be religious in nature. The book that alerted me to the concept, after all, is based on Bible stories, even though apparently there was no real evidence of Hebrew women in particular using menstruation huts or anything similar like the book describes, but whatever. There's history showing indigenous people in the US using similar facilities ages ago. Some pagan religions use and revere menstrual blood as magical. I once saved some in a Moon Cup to make paint out of it (it turns brown once it’s oxidized and isn’t as pretty as I expected it to be. Lesson learned. The brown-smeared canvas is hanging in our bedroom, anyway).

Some could be aimed at trans men and non-binary AFABs who want the community experience but without the conflicting male and female “energies.” Some could be “all-gender,” with the only requirement being that you have to menstruate while you're there. But sex-segregated facilities would need to be widely available and enforced for the safety and comfort of preteen and teenage girls and women.

And that brings me to my point: what good would bringing back the Red Tent do for young girls and women — and society — as a whole?

In the comments on Walt’s call for women Substackers to broach this topic,

hit the nail on the head:I appreciate this topic being broached, it’s important.

From my perspective and ‘becoming-woman’ experiences, I think I would have benefitted from a culture than has a mother in it. There’s alot of talk about absent fathers but if a girl can only draw her meaning/identity from a predominantly masculine symbolic then it is no wonder she feels alienated and lost with these developments. We need an initiation into becoming-woman just as men have desired that for themselves in becoming men. Menstruation was not really spoken about when I was growing up, it was an almost meaningless inconvenience, alongside boobs. I think the suggestion of gender segregation in regards to this cultural and imaginative lack has potential. I’m not talking about gender segregated toilets (I think this is where feminism goes to die tbh), I’m thinking more along the lines of the creation of a female to female culture where we feel safe creating meaning and talking about our bodies, giving us the confidence to relate to men in ways that don’t feel as hostile. Because ofcourse we are not always in a state of being alluring spectacles, even our cycles mean we have fluctuating modes of desire, we don’t feel consistently the same in our bodies through out the month. Me and my friends often discuss ‘monster mode’ (luteal phase) 😂 these experiences are not adequately symbolised.

We need coaching by the og boob bearers

Emphasis mine.

To put it simply, we need real female solidarity and sisterhood again. We need “The Aunties” back. We need to be able to teach our young girls what is happening to them and their bodies, and what to expect from men and how to handle it, in a safe space and with other women they can look up to and trust and learn from.

A space like this would have to be child-friendly. All genders, probably, up to around 5 or so like is commonly accepted in public bathrooms and such, then after that, only girls. Perhaps there would also be adult-only Red Tents for people like me who hate random screeching and messes and small humans bonking unthoughtfully into me, but I also think it would be beneficial for society as a whole for more women like myself to normalize and adapt to being around small children. For childfree people like myself who tend to make friends with similar people, children, and caring for them in any real capacity, can be very easy to avoid. And as someone who doesn’t want kids of my own, I understand the desire to have adult-only spaces and would never want to compel people to have children or take on the unwanted role of babysitter (please literally never ask me to babysit), but for this to be effective, young girls have to be taken under the wing of the women in the community, and so the child-free3 spaces shouldn’t be the majority of them.

This is very much sounding like a “it takes a village” argument, and I suppose that’s because it kind of is. There really isn’t a way to solve this problem without whole-community involvement.

There are a number of problems, snags, potential issues, political taboos, etc. that would prevent this from happening for real (like, who would even work at the more posh Red Tent facilities that provided more services? I'm having fun picturing the possible collection of staff at a place like this), but it’s fun to think about, isn’t it? A real sisterhood, the feeling of confidence and power in numbers, and the wisdom of older women to guide the younger generations. Maybe it won’t be a real Red Tent that does this for us, but whatever it is, we need to recreate that world of female wisdom and solidarity.

Finding a way to track periods to make this an accountable process would face serious backlash. From me, too, honestly. That shit just ain't safe right now.

See? Instant controversy.

Of course, “child-free” doesn't include literal menstruating children; I'm thinking more of unsupervised 7 year olds running around throwing hay and stuff

This is an amazing proposal.

I read "The Red Tent" back in 2013 when I was hospitalized for a week after having a nervous breakdown from the bad relationship I was in. It helped me recover and passed the time pretty quickly, and ended up being one of my favorite books.

I've also, in a weird way, had the red tent experience and think it would go a long ways towards making everyone a little more sane if it was normalized. My experience was just hanging out in a yurt with a bunch of other women in the summer of 2009 when I was having my period. We were drinking wine, eating chocolate, and having the most witchy conversations in there lol. It was freaking glorious.

I think your idea would truly solve a lot of issues.

Also I'm angry about how the early period thing causes shorter than normal stature and metabolic issues. I definitely ended up short and my boyfriend keeps giving me shit about how I eat like I have a disorder... yeah, I HAVE to eat like I have a disorder to not have runaway weight gain.

I never knew about the age getting earlier. Thanks for the information